A return to Red Bull DNA

RB Leipzig’s revival under Zsolt Löw and their push for Champions League qualification

RB Leipzig’s 2024/25 season had two faces. By spring 2025, the team’s form was very underwhelming: after a 4th-place finish last year, they fell to 6th in the Bundesliga, seven points off the Champions League spots. In the first 23 games under Marco Rose, Leipzig collected only 38 points and 10 wins – their lowest since promotion in 2016.

Rose himself admitted, “We are, of course, judged on results… At the moment we aren’t playing the stars down from the sky – it’s clear criticism and questions will follow”.

Indeed, with only one win in their last six league games and a staggering eight-game winless streak away from home, Leipzig’s season teetered on the edge.

From a tactical standpoint, Rose’s side had lost the edge that defined past Red Bull teams. Leipzig’s famed gegenpress and vertical attack had gone missing. RBLive summed it up: “Without Xaver Schlager, the transitions after winning the ball fail on counters and even against a deep block… Rose demanded more intensity, but that only goes so far”. In effect, Leipzig were struggling to generate ideas on the ball – often “spiraling” into panic after a couple of bad passes. The once-feared RB “pressing network” had fatal holes; as striker Jonathan Burkardt put it, the team still had “the DNA of gegenpressing and transitions,” but right now “the once-feared pressing net is full of holes” – “the opponents are not stressed, but our own players stress themselves out”. In attack, Leipzig lacked both creativity and efficiency, while defensively, they were not forcing turnovers high up the pitch as in past seasons. The result was a team miles away from the high-octane Red Bull trademark.

Leipzig’s hierarchy turned to Zsolt Löw – a familiar figure with deep Red Bull roots. Löw has the Red Bull persona: he previously served as an assistant under Ralph Hasenhüttl and Ralf Rangnick at Leipzig and even worked with Thomas Tuchel at PSG, Chelsea and Bayern. As Leipzig sporting director Marcel Schäfer put it, “the team now has to turn things around together with Zsolt”. The mandate was clear: preserve Leipzig’s ambitions (Bundesliga top-four and a Pokal run) by restoring the aggressive, vertical style long associated with Red Bull football.

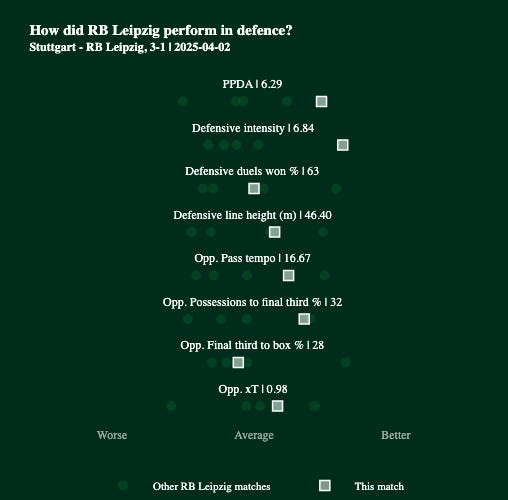

Löw’s first match came in the DFB-Pokal semi-final away at Stuttgart. With just two days’ preparation, Leipzig conceded in the 5th minute. The early goal was a blow, but Löw’s team kept its shape and created chances: Loïs Openda forced three saves from Stuttgart’s keeper Alexander Nübel in the first half, and Benjamin Šeško scored in the 62nd minute to make it 2-1. Yet Stuttgart showed characteristic RB-level intensity of their own: they immediately regrouped after Leipzig’s goal, won a loose ball, and Nick Woltemade finished their 2nd on 57’. Stuttgart then added a third in the 73rd (Leweling after a corner) to seal a 3-1 win. Leipzig had a foot in the final but fell short.

Afterward, Löw was honest yet measured: “The disappointment is bitter. In many areas we were better than Stuttgart… We tried to work harder in the second half”.

In that loss, signs of pressing were mixed. Stuttgart were aggressive, high pressing themselves (especially after going ahead), so Leipzig often played it safe out of the back. Still, Löw wanted more pressure: by the 60th minute, Stuttgart’s second goal was scored from a turnover in Leipzig’s half. The game underlined that while Löw’s ideas were taking hold, execution and experience were still lacking under intense pressure.

His first task was to reintroduce Leipzig’s traditional game plan: intense pressing and rapid transitions. He immediately reset personnel, recalling goalkeeper Péter Gulácsi and center-back Castello Lukeba to the lineup, and reverted to a classic Red Bull shape. In practice, this often looked like a 4-2-2-2 or 4-2-3-1: two holding midfielders providing a solid base and two forward players (often a central striker plus an attacking winger) tasked with running onto vertical passes. The formation on 11 April against Wolfsburg, for example, was listed as 4-2-2-2, a clear nod to the Rangnick/Marsch era setup.

Under Löw, Leipzig began pressing more organized and higher. The pressing triggers – moments when the team goes forward upon an opponent’s poor touch or back pass – were re-emphasized. In the first two league games under Löw, Leipzig won the ball aggressively and launched attacks. Against Hoffenheim, Löw’s side conceded an early goal, but after forcing a red card (Leo Østigård’s last-man foul), they seized the initiative. The team began to dominate possession and create more chances, scoring twice before half-time as their numerical advantage allowed a classic Red Bull press in Hoffenheim’s half. After halftime, even ten-man Hoffenheim showed spirit, but Leipzig punished them again in the 84th minute via an incisive counter: substitute Yussuf Poulsen finished a quick move.

A similar pattern emerged at Wolfsburg. Leipzig dominated the first half, mixing high pressure with vertical outlets. Loïs Openda scored after just 11 minutes and Xavi Simons volleyed in a second 26 minutes in. Statistically, Leipzig held 52% possession over Wolfsburg and created 16 shots (5 on target) to Wolfsburg’s 17 (6 on target) – a strong attacking return given it was an away game. Simons added a third goal in the 48th minute. Even as Wolfsburg clawed back with goals in the 58th and 75th minutes, Leipzig stayed in control, managing the game with the defensive solidity of a double pivot and the intensity of their press. After these two matches, Löw’s men picked up the full six points and had at least shown flashes of the high-press, vertical style long associated with Leipzig’s identity.

Early statistics under Löw (though still a limited amount of data) hinted at this shift. The quick returns by Benjamin Šeško and Ridle Baku in the Hoffenheim match – Leipzig’s first goals in five league games – pushed their expected-goals metrics up from the gloom of March. Possession stats and pass completion during high-pressure situations improved, for example, against Wolfsburg, Leipzig saw 52% possession and managed more successful tackles/pass recoveries in the final third than they had in any comparable game under Rose.

In midfield, Löw demanded quick, incisive passing. He insisted on vertical combinations when regaining the ball: the two holding midfielders (often Kevin Kampl and either Beier Švedkauskas or Yussuf Poulsen) would look to feed the attack. In the Hoffenheim game, for example, a Gulácsi long ball set up Šeško’s first goal. Wide players were asked to use their pace and press: David Raum was key to stretching the defense and delivering crosses.

Above all, Löw brought back the relentless gegenpress. In press conferences, he mentioned “aggressive pressing and counter-pressing” as a hallmark of RB football. He even praised the opposition coach (Dino Toppmöller) for demanding the same of Frankfurt, underlining how ingrained that philosophy is in the league – and in Leipzig’s approach. Löw lamented that defensive errors (two bad passes) could still trigger panic in his squad.

“When a couple of poor passes in succession happen, we start to spiral… We’re not yet a team that can easily put setbacks aside. We need to work on developing more stability”.

In other words, the intensity was back, but the composure needs work.

Löw’s message to his players – echoed after the Wolfsburg win and in training – was that togetherness and intensity must multiply their strengths.

“We need to rally together as a unit. That is what multiplies our strengths,” he said, emphasizing unity above all .

Tactically, this translates to one guiding principle: if one player presses or covers, his teammates must rotate and fill the space. In that sense, Löw’s style did not reinvent the wheel – it is classic RB Leipzig. At Bayern Munich, Nagelsmann once spoke of “RB DNA” as a constant, and Löw’s first weeks reaffirmed that DNA: vertical runs, fast transitions, and unified pressing. His football brain had been honed under Rangnick, Hasenhüttl, and even Julian Nagelsmann at Leipzig, so he defaults to the same playbook as those predecessors.

In interviews afterwards, Löw sounded pleased but wary. He highlighted the positives – a “great first half with three lovely goals” – and noted that Leipzig controlled those games much better than late March. He also praised his attackers’ work rate. Of Xavi Simons, Löw said:

“He has the quality and the character to become a leader”, adding that training and discussions with the young captain have been “very constructive”.

Löw’s comments on Simons showed a forward-looking mindset: building leaders in the squad rather than questioning effort.

Even as Löw’s Leipzig looked reborn in mid-April, questions remained. Leipzig played against Holstein Kiel. The result was a disappointing 1-1 draw, with Leipzig looking sloppy in spells.

Then came Eintracht Frankfurt on 26 April – a top-four rival and a stern test. Löw emphasized how critical those games were for Champions League qualification. But what unfolded was a disaster: Leipzig were thrashed 4-0 by Frankfurt. This loss exposed that the unit cohesion and tactical polish Löw tried to build not fully settled. Frankfurt attacked with pace and penetrated Leipzig’s midfield press; Leipzig’s own transitions broke down under pressure.

RB Leipzig - Bayern München

Zsolt Löw set his team up to run Bayern ragged from the first whistle. The hosts pressed in a flexible 4-4-2 (Šeško/Openda up front, Simons in the half-space, Seiwald/Kampl in midfield) and drew blood early. After a quick turnover, Xavi Simons played through Benjamin Šeško, who unleashed a superb curling finish into the corner in the 11th minute. Leipzig’s wide midfielders and full-backs then suffocated Bayern’s buildup, allowing Raum to whip in a set-piece that Lukas Klostermann headed home just before halftime. In the first 45 minutes, Leipzig dictated the game, limiting Bayern to only 36% possession and forcing eight saves from keeper Urbig on six shots. As Löw later put it, it was “an unbelievable game” that felt like “advertising for German football”. By the break ,Leipzig had stunned the visitors 2-0, taking the match to Munich.

After halftime, Bayern adjusted their approach (switching to a more aggressive press led by Goretzka and Kimmich) and poured on pressure. Eric Dier powered home a corner (62’) and Michael Olise drilled in the equaliser (63’). Statistics tell the story: Bayern surged to 64% possession and fired 19 shots (versus Leipzig’s 6). Leipzig, by contrast, dropped into a deep block and sat on the 2-0 lead, conceding midfield ground. The visitors took advantage: Leroy Sané crashed in at 83’, silencing the Red Bull Arena. Leipzig’s earlier confidence and pressing intensity evaporated. The defense, led by Lukeba and Klostermann, looked unsettled by Bayern’s sharp movement. It was as if their high-energy first half had drained out – they covered 123 km to Bayern’s 120 km (per Löw) but still trailed 2-3. RB’s one-dimensional passing (only 262 completed) could not break Bayern’s wave, and Leipzig’s attack went bland. In this chaotic second act, Bayern almost smelled victory; RB’s managing director Marcel Schäfer acknowledged that fighting back to draw was important – “every point counts” – but he admitted “mixed feelings” that a lead slipped away.

The finale was the stuff of nightmares for Bayern and ecstasy for Leipzig. Yussuf Poulsen, the substitute “joker,” seized a clever Simons pass and chipped Jonas Urbig at 90+4′.

In the press conference, Löw beamed that he was “incredibly proud” that his team never gave up “until the very last minute”. He joked he had even prayed to the “football god” when Bayern went 3-2 up, quipping that the divine intervention “gifted us the 3-3”. Leipzig’s fans, seeing their team wreck Bayern’s surprise party, celebrated (and on social media, trumpeted the spirit shown). Bayern’s camp was more stunned than angry: sporting director Christoph Freund praised the spectacle as an “awesome match” even as he lamented the late leveller, noting Bayern were still “effectively champions” for now. Eberl was blunt: he called Leipzig’s late goal “a lucky punch…annoying,” but reminded everyone that Bayern remained nine points clear.

Two months into Löw’s tenure, what can we say? On the plus side, Leipzig’s underlying numbers and performances improved from March. Goals are flowing again: 6 goals in the first half of April (Sesko, Baku, Simons x3, Openda, Poulsen) after going scoreless in five league games under Rose. Critical players like Simons and Poulsen are contributing. The pressing intensity is back – opponents can attest (even if sometimes luck prevails, as Hoffenheim showed).

Off the pitch, confidence seems healthier. Löw is reverting to the classic RB blueprint of “aggressive pressing and quick vertical play.”

Yet caution is warranted. The league table underscores how tight the race is: after 32 games, Leipzig has 50 points – 6th place – still outside the top four. Bayern and Leverkusen are well ahead, and fourth through sixth were separated by only one point each (Frankfurt and Freiburg on 51, Leipzig on 50 ). A slip-up or two could be fatal. The 4-0 loss to Frankfurt was a strong reminder that overcoming experienced coaches like Dino Toppmöller still eludes them when the plan misfires. Still, Löw remained optimistic. He reminded everyone that the squad has “five more finals” to play and that a Champions League place – worth an estimated €50 million in prize and TV money – is very much on the line.

From a strategic view, Löw’s approach is continuity with tweaks. He’s inherited a system, but he’s modernizing it. He trusts youth – developing players like Vermeeren and giving Vandevoordt confidence at goalkeeper, and he’s worked already to adjust in-game. For instance, he substituted well at Wolfsburg to see out the game. His emphasis on team stability and unity suggests training sessions emphasizing pressing drills and situational play, hallmarks of Red Bull methodology. If Leipzig can iron out late-game lapses (a consistent theme in all three defeats under Löw), they should live up to their potential.

Löw’s Leipzig feels like a team rediscovering its swagger. The Red Bull philosophy of high-intensity attack is once again on display, and Löw’s familiarity with that approach is yielding results. As Nagelsmann said when he joined Leipzig, “the RB DNA will continue to be our foundation” – Löw has embraced that fully.

The last few weeks of the season will show whether he can solidify this revival. For now, Leipzig supporters can at least breathe easier: after months adrift, the Bulls seem to be running again, and the Champions League dream remains alive